Share:

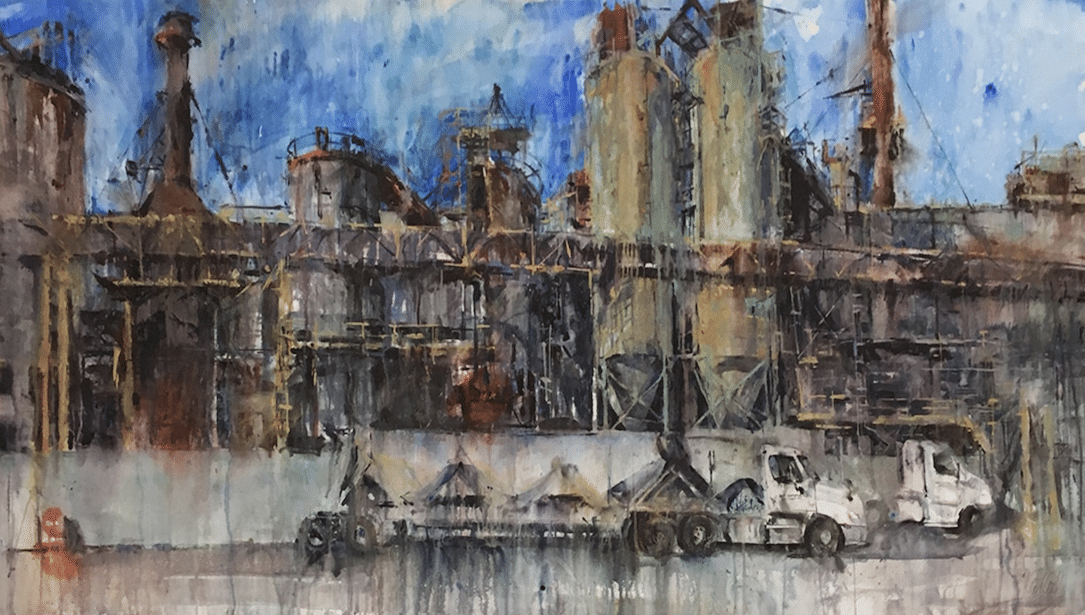

My style of watercolor painting can best be described as sophisticated chaos, where an accurate drawing gives way to an expressive painting to create a beautiful mess. I’ve recently begun painting large-scale works in the studio, which allows me to magnify my style to a whole new level, more like mammoth chaos. I can push everything about my work—more design, drawing, painting, paint, and effects. In this step by step, I’d like to share the process of creating a large-scale work which inspired by a large-scale site. I focus on design, drawing, and painting—regardless of the scale of the piece. Within the tight structure of the design and drawing, there’s great freedom to expressively apply paint—and lots of it.

Step 1: Design

My process begins with design. I used a large number of onsite sketches and dozens of photographs for GAF on Ponca, a 36 x 72″ painting based on a huge industrial plant in Baltimore, Maryland. I’m drawn to this particular site because of its interesting shapes, complexity of forms, and pure scale. The challenge is in capturing the feel, while not getting overwhelmed with the chaos. It is as much about what to edit, as it is about what to include. In Photoshop, I combine, distort, cut, paste, and move pieces, so that ultimately, the design is my own creation as much as that of the original source material.

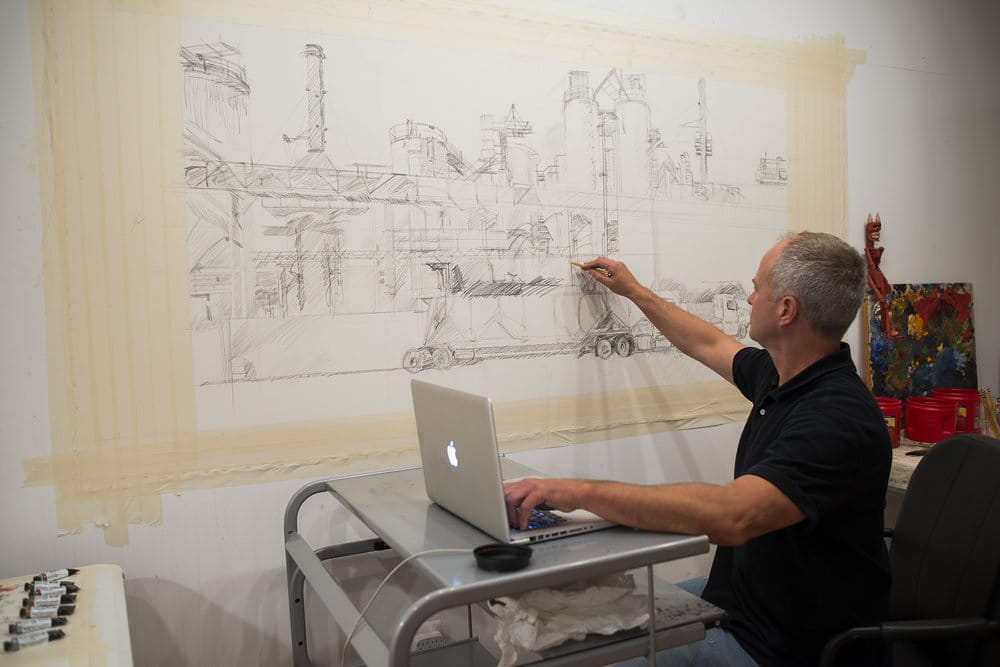

Step 2: Drawing

I use 140# cold press watercolor paper on a roll, wet it, and stretch it directly to the wall of my studio to dry flat and smooth. Using a carpenter’s level, I divide the sheet vertically and horizontally into quarters, so that I may translate my small-scale reference to a larger surface. I carefully build up the drawing, and shade areas freely, not concerning myself with any stray pencil marks. At this point, the focus is on providing myself guidelines as I paint, because I know things will get chaotic. Ultimately, many of the drawing lines may remain visible, as my finished piece is typically a marriage of painting and drawing. Once I’m happy with my drawing, and feel there’s enough information, I am ready to begin painting.

Step 3: The paints

For me, DANIEL SMITH Watercolors are an invitation to experimentation. After using other brands for years, I chose DANIEL SMITH for the quality of pigments and how they behave, but I also love them as much or more for how they misbehave, with the granulating effects and how they fall apart — beautifully — creating textures unachievable by any other means I’ve found with any other paints. With GAF on Ponca, I decided to really experiment by pushing the colors and effects, as the design seemed to require it. I chose to work with three color families — my standard palette of 14 colors, 15 PrimaTek colors, and another 10 iridescent colors. Some of the colors available with DANIEL SMITH are totally unique and desirable to that which I’m interested.

Step 4: First washes

I begin painting initial washes using large squirrel-hair mop brushes and attack the sheet as fast as possible, blocking in areas with clean color, and retaining critical areas of the white of the page. I use lots of paint and lots of water. I’ll splash water with my fingers, and even apply paint directly from the tube, and scrub it with my fingers. If I’ve gone too far, if there is such a thing, I simply use my spray bottle as an eraser and spray passages off. Typically, this may take 10-30 minutes depending on the painting, but at 18 square feet, this piece admittedly required more time and work. I add by brushing pigment and subtract by spraying water, scrubbing with brushes and even my hands, creating effects in any way possible and with any means necessary. I continue to paint, build, modify, define, create, destroy, add, and subtract, until it’s time to step away and let it dry for the night.

Step 5: Maximizing effects with PrimaTek

In the beginning, I look to achieve as much action on the page as possible, with lots of variety of color and maximum effects — more is more. I work to connect the separate islands into masses, and work towards relating unrelated areas. I’ll wet areas, scrub them out, add and subtract, create and destroy, and repeat over and over, modifying the whole time. This phase is incredibly frenzied, frenetic and even physical. I use several of the PrimaTek colors applied thickly, adding water on the paper to take advantage of the granulating effects. I mix directly on the paper, and allow the paint to drip, run and splatter as it will.

Step 6: Add shimmer with Iridescents

Using DANIEL SMITH Iridescent watercolors make possible the subtle shimmers of metals in golds, silvers, coppers, and even blues. I apply glazes using several iridescent colors, mixing them into other colors or using directly as is. After working into a wet painting, it can be misleading as what’s really happening. Entire passages may appear muddy or overworked when the iridescents are very translucent. However, having allowed the painting to dry, what’s left behind is pure, rich, and beautiful, and the painting appears fresh, bright, and reflective. One can literally see the flakes of iridescent particles sitting on the surface of the earlier layers of paint and it creates an absolutely stunning effect.

Step 7: Refinement

As I move on, I must be more judicious as to what remains and what disappears. I work on levels of contrast from dramatic to nuanced. I use stiff synthetic brushes, soft synthetic sable liners, spray bottles, my fingers, my fingernails, palette knives and paper towels. I’ll apply passages and marks of dark, scratch out areas of light, continue to build and refine. I never follow a so-called linear process, as even after this stage I may apply washes, scrub areas out, add, and subtract. I’ll dress up the painting with the final jewelry, including pipes, handrails, wires, and various marks. I don’t paint in a traditional sense of light to dark, but rather light AND dark, building opaque over translucent, and vice versa, until I reach a sense of completion.